Blog / Knowlegde Bites

A 15-year retrospective of European elections: women’s political participation and representation

The elections for the European Parliament are just around the corner. From June 6 to 9, EU citizens are called upon to cast their vote in the European elections. This vote determines who is elected as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP), working on legislation that affects the daily life of Europeans, including laws regarding climate, economic, and security policies. Thus, voting in the European elections can have a great impact. But do Europeans exercise their right to vote and are there differences between men and women? And are there gender-specific differences in the composition of the European Parliament?

Turnout in European elections

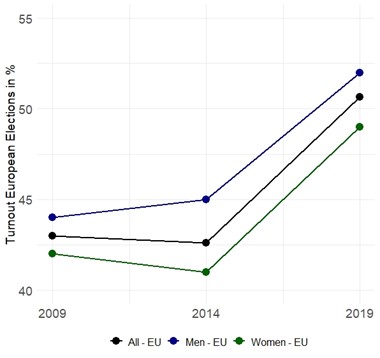

The last European Elections in 2019 saw a sharp increase in voter turnout. Figure 1 illustrates that around 43% of eligible voters cast their vote in 2009 and 2014 (black line). In 2019, more than half of those eligible to vote in the EU did so. The rising turnout suggests that EU citizens increasingly care by whom they are represented in the European Parliament. However, turnout in European Elections is still substantially lower than in national elections. There are also large differences across the EU regarding the turnout in European Elections. In some member states, voting is compulsory, for example in Belgium and Luxembourg, reflected in a voter turnout of over 80%. In other member states voting in European Elections is less established. For example, Slovakia exhibits the lowest turnout rate in all three elections. Only 20% of Slovakian voters cast their vote in 2009, 13% in 2014, and 23% in 2019.

Women and men at the voting booth

In national elections, gender differences in turnout have decreased or even reversed over time. Today, the turnout of women in national elections tends to be equal to or higher than that of men, while the opposite is true for European elections. From 2009 to 2019 the share of men voting in the European Elections (Figure 1, blue line) was always higher than the share of women (Figure 1, green line). The differences are rather small but persist over time. Again, there are large differences between countries. For example, in 2014, the gender gap was particularly pronounced in France (women: 37%, men: 49%) and Portugal (women: 28%, men: 40%), while substantially more women than men voted in Sweden (women: 59%, men: 43%).

Figure 1: Turnout in European elections in 2009, 2014, and 2019

Female representation in the European Parliament

These gender differences can not only be observed among voters. Women are also less represented in the European parliament. While it is possible that men also represent the interests of women, there is evidence that female MEPs are more likely to act in women's interests. Even though the share of women in parliament has steadily increased over the last three European elections, it is still not balanced. At the start of the current legislative period, the share of female MEPs amounted to 40%. As of 2023, this puts the European Parliament above the European average regarding female representation in national parliaments. There, the proportion of female members of parliament ranges from 57% in Finland to 15% in Romania.

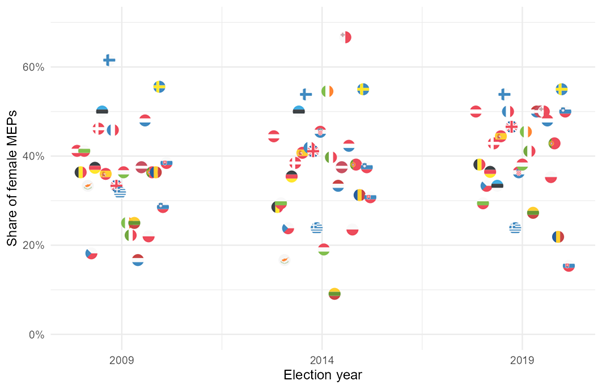

However, as Figures 2 and 3 show, there is also significant variation in the share of women in the European Parliament depending on political groups and their country of representation. Figure 2 shows the share of female MEPs by country. It ranges from 9% in 2014 for Lithuanian MEPs to 67% for MEPs from Malta. While the share of female MEPs from Scandinavian countries is consistently high over the last 15 years, there is also a general upward trend towards gender balance.

Figure 2: Share of female MEPs in 2009, 2014, 2019 by their country of representation

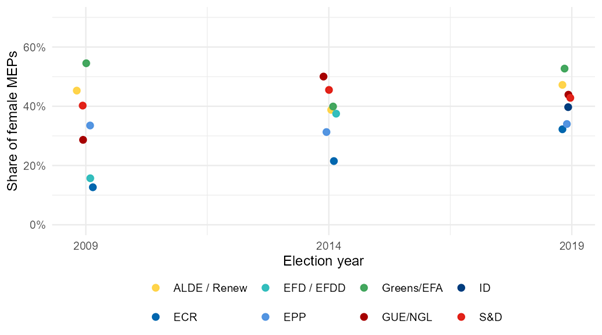

Figure 3 shows the share of female MEPs by political groups. These groups are formed by national political parties with similar political interests. In 2009 and 2019, this share was the highest for the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA). This political group consists primarily of parties with a focus on environmental politics. Overall, we see relatively more female representation in left-leaning and liberal political groups. This includes the Greens/EFA, the Left (GUE/NGL), the Social Democrats (S&D), and Renew Europe (ALDE/Renew). Contrary, there is a tendency for lower shares of female MEPs in Eurosceptic, conservative, and right-leaning political groups, such as the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), Identity and Democracy (ID), the European People's Party Group (EPP), Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) and its successor Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD). The differences among political groups in the European parliament also decreases from 2009 to 2019 and move towards more gender balance.

Figure 3: Share of female MEPs in 2009, 2014, 2019 by political groups

The upcoming European elections

Given that women are still less likely to vote in European Elections and are still underrepresented in the European Parliament, it is even more important to vote in the upcoming election. To get an idea of who best represents your preferences, you can use the EU&I voting advice application. It is available in all European languages and compares your own preferences not only with the standpoints of the parties in your country, but across the European Union.

Milena Rapp is a doctoral researcher at the Mannheim Centre of European Social Research and the Graduate School of Social Sciences of the University of Mannheim.

David Schweizer is a doctoral researcher at the School of Social Sciences and the Graduate School of Social Sciences of the University of Mannheim.